Kuusijärvi nature and history

The intriguing history of Kuusijärvi is full of kings, tragic maidens and a horse rider who lost his sword. The name of Kuusijärvi (“Spruce lake”) comes from a small lake surrounded by spruce trees.

The name of Kuusijärvi

The old Swedish name of Kuusijärvi, “Hanaböle träsk”, suggests that most of the lake belonged to the village of Hanaböle. It was Hanaböle’s small freshwater lake which is “träsk” in Swedish. The name Hanaböle träsk appears on local maps from the 1700s. However, the lake did not belong to Hanaböle alone since its easternmost side was part of the village of Sottungsby or Sotunki.

The Finnish name Kuusijärvi was coined later. A railway that was built in the 1860s resulted in an increasing number of Finns moving into the area. Many of them went to the lake for a swim and since it was a small lake surrounded by spruce trees, they started to call it Kuusijärvi (“Spruce lake”). This name has been in use since the 1920s if not earlier.

Ice lifting

Local farms used Kuusijärvi for ice lifting purposes. Before fridges were invented, people had to collect ice in the winter to keep milk from spoiling in summer. Chunks of ice were cut from the lake. First, a hole was made in the ice and then it was cut using a heavy-duty ice saw. Once cut, the chunk was lifted from the lake with wooden beams and ice hooks. A horse and sleigh were used to transport the ice to farms. The ice was usually covered with sawdust. If the ice was well covered, it would keep for the whole summer until the following winter when new ice was collected. At least the farms in northern Sotunki took ice from Kuusijärvi.

King’s picnic lunch

Nowadays, Kuusijärvi is located in Kuninkaanmäki district. The hill which gave its name to the entire district of Kuninkaanmäki (“King’s Hill”) is located right on the eastern side of Kuusijärvi. It is the hill where His Royal Majesty Gustav III sat on 10 June 1775 on bare ground eating lunch. The spot is marked on both Nils Westermark’s map from 1777 as well as C. P. Hagström’s map from 1778. The name of the district stems from this event. According to the maps, the picnic spot was located in a depression between the cliffs which is now full of detached houses. In theory, however, you could imagine that the king would have climbed onto the hill to admire the views while eating his lunch.

History in pictures

Suuri Rantatie (the Great Shore Road, a section of the King’s Road postal route)

Kuusijärvi was located fairly far away from the residential areas of Hanaböle and Sottungsby. A remote location means that there are no known signs of permanent residence in the vicinity of the lake. However, the Great Shore Road, also known as the King’s Road, is 300–400 metres east of Kuusijärvi.

The Great Shore Road was the road that connected the Turku and Vyborg castles. The road’s exact time of construction is unknown. However, the locations of the bridges follow the shoreline of the 800–1200s. Tapio Salminen, who has conducted research on the topic, thinks that the road’s bridges would have been in use since the latter half of the said period. It is thought to have become a public road at the time of Vyborg Castle construction in the 1290s at the latest. The road served as an administrative and military link between the Turku and Vyborg castles. The 1290s period coincides with the organised movement of Swedish migrants to Uusimaa which seems to have taken place either at the end of the 1200s or the beginning of the 1300s.

The road has been called the Great Shore Road but the name King’s Road was also used. However, the name King’s Road does not refer to kings using the road but is rather a term used in relation to construction and maintenance. The roads of King’s Road connected different regions with each other. They were at least ten ells (5.94m) wide and had inns along the way.

Neidonrinne (“Maiden’s Slope”)

A short distance north from the king’s picnic spot along the Great Shore Road is a hill named Brudbrinken. A book published in 1928, which is part of the Finlands Svenska Folkdiktning series of cultural history stories collected by V. E. V. Wessman, describes how a maiden rode to her death on the hill. Ethnologist Bo Lönnqvist received similar information about the area whilst collecting names in 1963: “En brud har ridit ihjäl sig där, på den tiden då det inte fanns några vägar enl. gammal folk”. A maiden rode to her death when roads did not exist.

According to Ulpu Lehti, place names with Brud appear in Swedish-speaking regions and the word is often linked to some catastrophe. The word Brud is very often related to a story of a maiden who lost her life. This is a naming convention and efforts to find evidence of a young girl’s horseback accident would be in vain. Likewise in Finnish-speaking areas, place names with the words Tyttö, Neito and Impi are often connected to stories involving an accident.

Even if there was no actual fatal accident, the name Brudbrinken still describes a dangerous point in the road. It seems that the Brudbrinken hill was one of the most notorious hills along the Great Shore Road. The Provincial Governor ordered a search in the area back in 1777 and the road alignment was changed as soon as the following years. The old alignment that was abandoned at the end of the 1700s still exists and is used as a ski track in winter.

A sword was also discovered near Brudbrinken. The sword’s pommel was discovered with a metal detector back in 2010 and the rest of the sword in 2012 when the same person went to search the area again. It is most likely a sword from 1710–1840 that belonged to a Swedish infantry officer. Why the sword ended up on the ground is a mystery. The sword can now be found in the collections of Vantaa City Museum.

Winter road

In an old map from 1777, a road forks off the Great Shore Road towards the east to the village of Sotunki a little after the king’s picnic spot. The road was titled “Winterväg åt Sottungsby” which means “winter road to Sotunki”. When horses were used for transport, different roads were typically used in summer and winter. The summer roads were usually humble paths that were not fit for a carriage.

The winter roads often crossed frozen wetlands and were more durable than the summer roads. For this reason, it was ideal to transport heavy loads in a sleigh along the durable winter roads in winter than on wet sludgy roads in summer.

Nöje, Mariedal glass factory and Myras inn

Several historical points of interests are located north of Kuusijärvi along the Great Shore Road. Nöje, one of Vantaa’s oldest buildings, is located in Kuninkaanmäki. Mariedal glass factory is related to the story of Nöje. Its ruins are in what is now Sipoo. The glass factory was founded by Johan Sederholm, a merchant and the owner of Håkansböle manor from Helsinki. The glass factory operated in the area in 1782–1824.

Sederholm commissioned German brothers Johan Anders and Gottfrid Schmidt to work as glassblowers in the factory. Johan Anders became wealthy and, according to knowledge passed down, transported the old main building of Hanaböle Heikas closer to the glass factory to be his hunting cabin. He christened it Mitt Nöje, which is Swedish for My Pleasure. This is how the Nöje estate got its name. An old building which was most likely built in the 1700s and transported there by Schmidt is still standing on the farm.

Mariedal glass factory no longer exists. These days, there is a barn where the factory used to be. There is also an interesting mound next to the barn which could be related to the factory somehow. There are signs of the glass factory in the surrounding field as it contains large amounts of brick, glass, quartz and slag glass. The factory flourished in 1808 and 1809. However, it faced difficulties after the Finnish war and was closed entirely in 1824.

Moreover, along the Great Shore Road between Nöje and Mariedal glass factory used to be Myras inn. The inn can be seen on old maps but has since disappeared without a trace. Modern houses are built in its place.

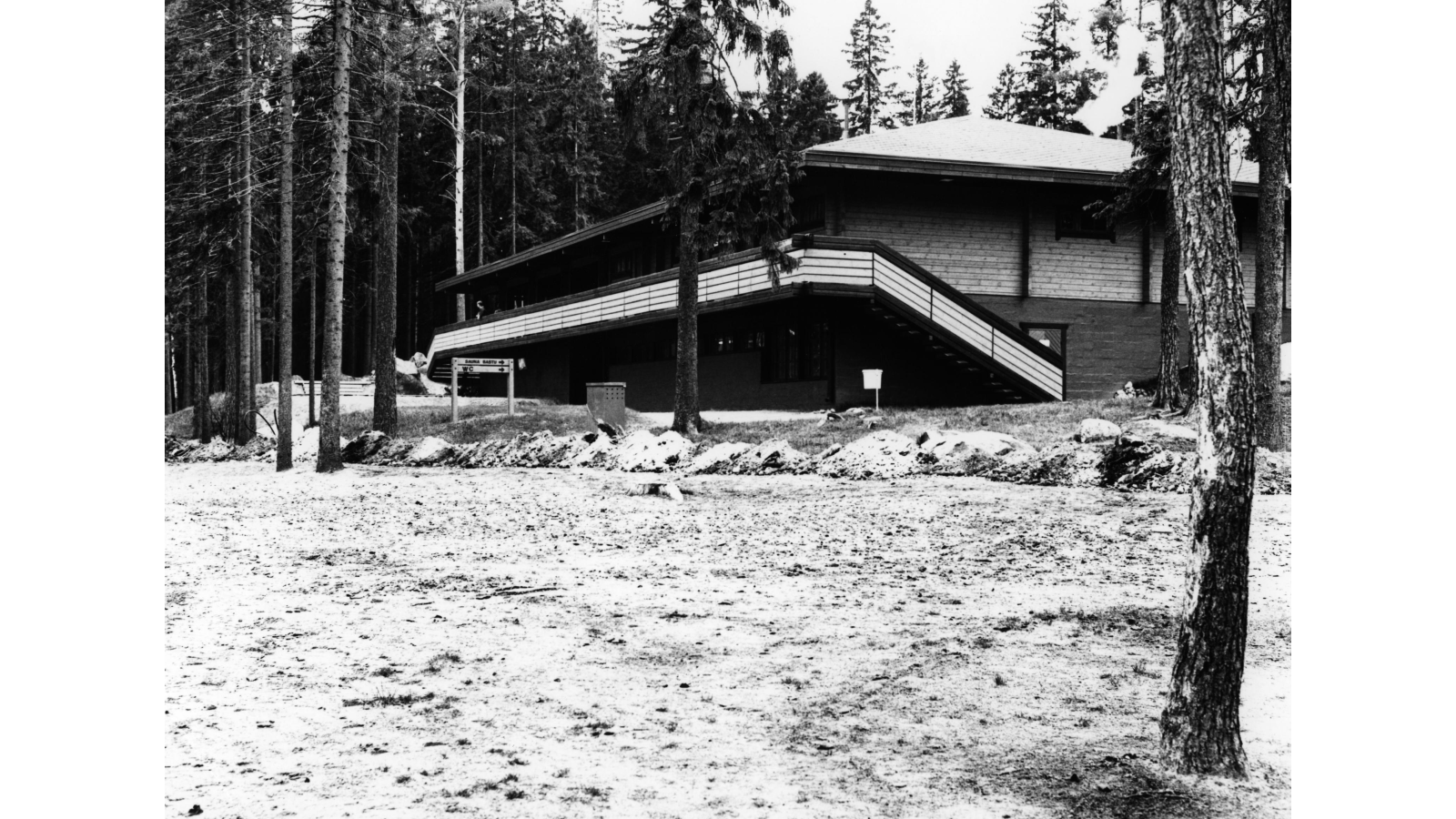

Kuusijärvi becomes a recreational area

The evolution of Kuusijärvi into a recreational area is the result of societal changes in the 1900s. First, the area surrounding Kuusijärvi was purchased by the estate agent Svenska Småbruk och Egna Hem in 1907. The company donated the land area to Svenska Odlingens Vänner i Helsinge (SOV), an association that fosters Swedish-speaking culture, in 1924 with the condition that the association must maintain it as a nature conservation area. The area was protected under the Nature Conservation Act in 1936.

As the town’s population grew, beaches were in short supply. The region’s citizens used the beach at Kuusijärvi despite the fact that it was now a nature conservation area. In the end, SOV sold the area to a rural municipality in 1966 and the provincial government decided to end nature conservation in the area in 1968. Hanaböle träsk was the first area that was protected under the Nature Conservation Act in the rural municipality of Helsinki and it remained protected for over 30 years.

The construction of Kuusijärvi recreational area began in the 1970s. In 1970, a car park was constructed, lakeside paths were created, the beach was sanded and a playground for children was built. The work continued in the following years and an outdoor cabin was built in 1979.

Kuusijärvi logo symbolises lakes and deep forests

A logo and visual identity were designed for the Kuusijärvi nature and recreational area in 2022. The logo of Kuusijärvi is part of the city of Vantaa’s branding. The logo consists of two abstract shapes. They symbolise the surrounding nature and lake as well as the deep forests and cultural landscapes of Sipoonkorpi National Park.